We've completely run out of water. I appeal to the centre with folded hands to immediately intervene and get munak canal started in Haryana

— Arvind Kejriwal (@ArvindKejriwal) February 22, 2016

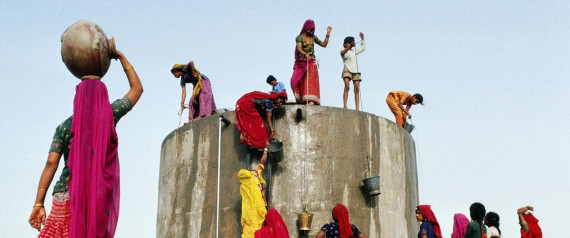

This tweet from Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal is a forensic moment for India's water sector. Jat protestors demanding reservation in Government jobs had dismantled sections of the Munak Canal, which supplies 60% of water to Delhi. Two thousand soldiers from the Central Reserve Police Force, drawn from 20 companies, were needed to recapture, repair and protect Delhi's lifeline. But in that brief moment, the water poverty of the nation's capital was revealed. In fact, in the last few years, several such forensic moments occurred across the country. The highly polluted Varthur and Bellandur lake spewed toxic 'snowy' foam on to the streets of Bangalore, while Chennai, in blind pursuit of real estate development, suffered its worst flood ever.

The urban rich in India are growing. Coupled with that is their thirst for golf courses, swimming pools, luxury bathrooms and water amusement parks.

However, celebration trumps introspection in the run-up to World Water Day (March 22). Newspapers and television are flooded with advertisements from government and corporate entities tom-tomming their commitment to water conservation. As the din dies down, so do hopes of managing water wisely. Here, we turn the spotlight on five blind spots to India's water challenge.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

1. Water orgy of the urban rich

The urban rich in India are growing. Coupled with that is their thirst for golf courses, swimming pools, luxury bathrooms and water amusement parks. The water orgy of India's rich is on full display in the state of Maharashtra, where villas promise a swimming pool on each floor while 7000 villages face acute water scarcity.

However, fetishizing supply is preferred over regulating demand. From desalinization plants, to interlinking rivers to the promise of 24x7 water supply, our politics legitimize solutions in the name of the common man, but in reality, supply water to the rich. The litigation and conflict surrounding the diversion of water supply from the city of Pune to the expensive real estate destination, Lavasa City, is case in point. In Delhi, the rich have cornered the bulk of the city's water supply by paying private water tankers, digging illegal bore wells and bribing officials.

The 24x7 water supply system was made operational for some of Delhi's extremely posh colonies... people promptly switched to washing their imported cars three times a day.

Some believe that making the rich pay for their water will solve this problem. Reality disagrees. The 24x7 water supply system was made operational for some of Delhi's extremely posh colonies with the belief that regular supply and volumetric pricing would lead to better water conservation. In fact, as the buzz goes, people promptly switched to washing their imported cars three times a day and watering the lawns more frequently. Such pathology of water consumption by the rich remains unexamined and hence, untreated.

2. Local water availability

Big-ticket water infrastructure projects have never been the silver bullet, despite claims to the contrary. Take the case of Delhi for example. A whopping 87% of the total water distributed by the Delhi Jal Board is supplied through two canals. One passes through Haryana and the other through Western UP. Political agitation in these two states can cripple the city.

Or take Veeranam Lake. Located 235km from Chennai, it finally started providing water to the parched city after almost 40 years since its conception and is still not proving to be enough! Chasing pipe dreams takes us further away from our cities, while little is done to improve local availability of water.

Relegating local water harvesting to policy backbenches will soon prove costly.

Water harvesting and groundwater recharge, being small and inexpensive, are considered politically inopportune. It is also argued that they cannot ensure self-reliance. However, they can play a critical role to help reduce the water poverty of Indian cities and towns. This has been successfully proved in the Mazhapolima project in Thrissur district in Kerala. Harvested rainwater is being used for recharging dug wells to improve local water security. Relegating local water harvesting to policy backbenches will soon prove costly.

3. The convenience of uncertainty

From melting Himalayan glaciers to erratic monsoons to El Nino, the impacts of climate change in India are unravelling in strange and complex ways. However, while scientists at IPCC are still grappling with the uncertainty of climate change, politicians in India are engaging with it with great certitude. It is emerging as a handy smokescreen to administrative and planning failures.

From the tragic floods in Uttarakhand in 2013, to droughts in Maharashtra in 2013 to the Chennai floods of 2015, every state government has steadfastly pointed at climate change. However, experts have repeatedly pointed out that in each case, riverbank encroachment, sand mining, rampant construction of dams, perverse incentives to water hungry crops like sugarcane, illegal sewage connections and real estate development on wetlands, all were far more abnormal and damaging than unexpected rainfall.

[Climate change] is emerging as a handy smokescreen to administrative and planning failures.

While there is absolute certainty that climate change is a clear and present risk, we need to realize that corruption and negligence will serve to amplify damage from it. However, state governments are more interested in chasing after silly and expensive measures like cloud seeding, rather than clamping down on corruption and climate-insensitive planning.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

4. Poor management and accountability

Who exactly is accountable for achieving water supply goals in India? Since water is on the state list, it should have been an easy answer. Unfortunately, that is not the case. Take rural water supply as an example. Panchayats are empowered only in letter under the 73rd Constitutional Amendment to plan and manage their water sources. In practice, it has become an excuse for the Union and state governments to abdicate their responsibility to provide reliable drinking water supplies. Hence, panchayats are reduced to becoming government contractors for yet another scheme. Taken with the government's idea to promote piped water schemes, people who are generally untrained, unaware of government programmes and unable to deal with a complex system such as piped water supply are now supposed to plan, maintain and monitor them.

Panchayats are empowered only in letter under to plan and manage their water sources. In practice, it has become an excuse for [governments] to abdicate their responsibility.

Public service agencies like the Public Health and Engineering Department (PHED) and urban water utilities are grossly understaffed and woefully incapacitated. And when they do work, the lack of communication makes things worse. Such a tragedy of errors played out in front of hapless citizens of Bangalore, where the Bangalore Development Authority and the Mahanagar Palika were busy laying out water supply and drainage lines without even informing the city's water supply and sewerage board. Needless to say, hydro-bureaucracy in India requires a serious revamp.

5. A question of quality

Water quality remains a blind spot for both suppliers and consumers. The government's estimate is that about 70% of all water in the country is unfit for direct consumption without treatment. Most people feel water is safe to drink if it's clear and does not smell. Sadly, this is not true. Arsenic, fluoride, bacteria and other contaminants are invisible and do not smell. Service providers such as urban water utilities test water at point of supply, and in rare cases, a few patchy samples at point of use. Similarly, in rural areas, PHEDs typically test a water source at installation and rarely come back. Panchayats are given field test kits by the state and district water missions so they can monitor water quality. Not knowing how and for what to use it for, most of them lie unused.

Most people feel water is safe to drink if it's clear and does not smell. Sadly, this is not true.

The knowledge gap on water quality is something that the urban rich and the rural poor share in equal measure. Sadly, while the rich can try and buy their way out by investing in expensive water filters, our rural populations are being condemned to drink unsafe water. Unless water quality issues are addressed we will continue to subject our citizens to contamination.

In conclusion

There is definitely a crisis of water in India. But it is always articulated within the narrow confines of 'shortfall' and 'scarcity'. This helps justify public support for converting rivers into plumbing projects, setting up expensive desalination and reverse osmosis plants and seeding clouds. We are ignoring the fact there is a serious crisis of management, of over-consumption, pollution and worse, glaring inequity of water access by the poor. With World Water Day around the corner, we'd like to ignore the scaremongering about the world running out of water, and ask instead if along with water, wisdom to manage it is also in short supply.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook | Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter | Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Also see on HuffPost: