Co-authored with Raunaq Chandrashekar

A stormy Winter Session of Parliament concluded on 23 December. While it saw the passage of several vital legislations, we unfortunately witnessed five trends that plagued the Parliament's functioning. These trends strike at the heart of a deliberative democracy and its legislative machinery, warranting a close look and some thought.

1. Undue stalling of parliamentary business

In the context of the National Herald case, this Winter Session culminated in a logjam for several days in both houses of Parliament. The complaint implicates Congress Party President and Vice-President, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi. As a result, the Congress-led opposition disrupted parliamentary business, with cries of foul play and political vendetta.

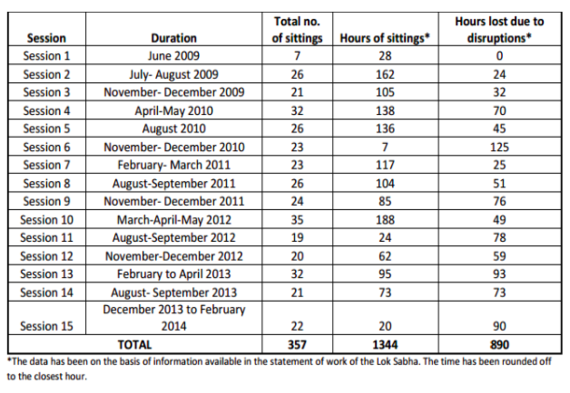

Disruptions to Parliament are not new. During the UPA-II regime, the BJP-led opposition was guilty of employing the very same tactic to great effect. Owing to disruptions, the 15th Lok Sabha functioned at only 61% of its productive time, while the Rajya Sabha functioned at 66%.

Arun Jaitley would famously go on to defend parliamentary disruption as a legitimate tactic arguing:

![2015-12-30-1451470745-4678369-ScreenShot20151230at3.48.05pm.png]()

The question we are forced to ask, therefore, is not whether disruption is a legitimate tactic, but whether its use as a tactic in a particular context is legitimate or not. In the preceding Monsoon Session, disruptions were made to initiate inquiries against the Madhya Pradesh government in light of the Vyapam Scam as well as Sushma Swaraj and Vasundhara Raje over LalitGate. Now, by Jaitley's logic, to disrupt Parliament over 40 mysterious deaths, or the Foreign Minister's role in abetting an economic offender's escape, might appear (subjectively) valid and legitimate.

In this session, disruptions over the constitutional crisis in Arunachal Pradesh may also be justified as it brought into light an issue that was otherwise being ignored. However, the other motivations for disruption can be termed vague at best and nebulous at worst. The fact remains that the alleged "political vendetta" was a judicial matter. The spillover into Parliament seems unwarranted, particularly when several government leaders in both Houses were happy to invite questions and debate on the issue.

In private, the younger brigade of Congress MPs admit that disruption shouldn't have gone on for more than three days. Furthermore, to disrupt Parliament over petty issues like Kumari Selja facing intolerance in a Gujarat temple and Jaitley calling her a liar, seemed ridiculous.

Similarly, on 22 December, after the passage of the Juvenile Justice Bill, the opposition wanted to adjourn for the day, but the government was keen on progressing with the passage of the next bill. The opposition, clearly in no mood to work for a few hours more, proceeded to the well of the house shouting slogans asking for the resignation of Finance Minister Arun Jaitley over the DDCA scam.

This winter session, parliamentary disruption had clearly overstayed its welcome. As a consequence, the productivity of the Rajya Sabha stood at only 46% with the passage of only nine bills, with several key legislations, such as the Real Estate Bill, Whistleblowers Bill etc not being passed.

2. Legislating without debating

Ironically, while the BJP lambasted the Opposition for foul play and the use of disruptive tactics to evade debate, the other major issue that plagued this session was the lack of debate in the Rajya Sabha on several important bills. Interestingly, the government and its floor managers were actively campaigning to pass bills without debate.

In the Rajya Sabha, several important legislations like the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Bill, Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Bill, 2015, Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2015 and the Atomic Energy (Amendment) Bill, 2015 were passed with no debate.

The word "Parliament" has its etymological origins in the French and Latin words for "talk", which best exemplifies the true nature of the institution as the deliberative pillar of any democracy. Parliamentary democracy is based on the idea that a process of debate and discussion must buttress any State decision. This process seeks to hear from every side of the political spectrum.

In the historical context of India, nothing exemplifies this better than the Constituent Assembly debates, which were the precursor to our Constitution. The Constituent Assembly debates lasted almost three years, yet the Constitution saw its first amendment as early as a year after its implementation.

This is clearly indicative of democracy as a dynamic process rather than an end in itself, and that dialogue is what drives this process. It is therefore a truism that legislative and policy decisions must be preceded by debate and discussion. However, this session saw a clear abdication of this duty on the part of our MPs.

3. Media influence precluding a balanced debate

In the context of the Juvenile Justice Bill, we witnessed the Parliamentary deliberation being adversely affected by a partisan media. While the more fundamental question surrounding the age of a juvenile might be a fair one to determine, the Parliamentary process failed to facilitate an unbiased and well-reasoned assessment of the question.

This can be attributed largely to the mainstream media, which had a hostile approach towards the issue. This is despite the fact that the Bill would not apply retrospectively to the juvenile in the Nirbhaya case. As a result of the intense media campaign, the BJP government decided to not pay heed to the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development's report, which rejected the bill, citing several constitutional infirmities.

Furthermore, discussion remained largely hyperbolic and hasty, while the proposals to send the Bill to a Select Committee were rejected. An MP told us in a private that while he was fundamentally against the JJ Bill, he feared being labelled "pro-rape" by his political opponents and the media. It was this fear and aggressively "pro" stance from the mainstream media that pushed a rather one-sided view through the Parliamentary process.

The Bill posed a complex question that struck at the moral and constitutional fibre of the nation, warranting a far more extensive and balanced analysis. However, the mainstream media failed to provide that, capitalising on public sentiment, which led to the government and opposition succumbing to a less than informed public demand. In the context of the release of the juvenile convicted in the Nirbhaya case, the media perpetuated a one-sided perspective, which invariably led to a frenzied public campaign and hasty decision-making.

While one can argue whether the consequences of such a law are good or bad, one certainly can't deny that the means of enacting it were problematic.

As Narayan Ramachandran writes in Mint:

4. Poor floor management

The winter session was witness to poor floor management on many occasions. For example, on the last two days of Parliament, we saw three supplementary additions to the List of Business, in addition to the Revised List. The Payment of Bonus Bill was brought in for passage on the afternoon of the 23rd and passed in a few minutes without debate! By the lunch break, the Congress senior leadership in the Rajya Sabha were left scampering for a bill brief to review whether the Bill had any controversial aspects before formulating their party position.

![2015-12-30-1451467997-2993993-ScreenShot20151230at3.02.32pm.png]()

In the Rajya Sabha, the Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Bill 2013 ended up having to go the Select Committee after it was pointed out that some of its provisions clashed with those of the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act 2013. This is poor management and should have ideally been anticipated by the government before listing it for consideration and passage. Oversight like this is an impediment to an efficient Parliamentary process.

The Finance Minister also introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code and a Joint Committee has been set up to review the amendment, in relation to conflicting laws. When the Bill is passed in the budget session, this would be a vital reform as Indian PSUs are currently saddled with NPAs. However, within two days of introduction, the government was looking to pass the bill. This is an unwelcome move and MPs should ideally have been given enough time to study the finer details.

5. Parliamentary intolerance

The other big disappointment this session was Shashi Tharoor not being allowed to introduce his Private Member's Bill (PMB). Congress MP Tharoor was going to introduce a PMB to amend Section 377 of the IPC and decriminalise "consensual sex between consenting adults". However, just when he was about to introduce the Bill, BJP MP Nishikant Dube decided to prevent him, and after calling for a vote in the house (71 against, 24 for), Tharoor's Bill was disallowed even from introduction.

Tharoor clearly didn't see that coming and had no time to rally for support. Attendance is usually low on Friday afternoons as MPs fly back to their respective constituencies after attending question and zero hours. PMBs are introduced every alternate Friday and introduction of this Bill would not have in any manner meant an immediate amendment to Section 377.

To not allow the introduction of a PMB is arguably the highest form of parliamentary intolerance. Even the introduction wouldn't have assured a discussion. PMBs for discussion are chosen through a ballot, and as legislative analyst Aparna Gupta puts it, "the chance of a bill coming up for discussion is harder a gamble than hitting a jackpot in a casino slot machine."

If a Bill does eventually come up for discussion (it is valid for three years after introduction), passing it is an even more herculean a task. Since independence, only 14 PMBs have been passed. The almost unanimous rejection of the Bill is surprising as PMBs are not "political" and a party stand or whip are not in play, at all. Employing such an aggressive stance seemed unfair to Tharoor, proving to be yet another instance of the majority being unnecessarily parochial and regressive.

![]() Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

![]() Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact HuffPost India

Contact HuffPost India

Also on HuffPost:

A stormy Winter Session of Parliament concluded on 23 December. While it saw the passage of several vital legislations, we unfortunately witnessed five trends that plagued the Parliament's functioning. These trends strike at the heart of a deliberative democracy and its legislative machinery, warranting a close look and some thought.

1. Undue stalling of parliamentary business

In the context of the National Herald case, this Winter Session culminated in a logjam for several days in both houses of Parliament. The complaint implicates Congress Party President and Vice-President, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi. As a result, the Congress-led opposition disrupted parliamentary business, with cries of foul play and political vendetta.

The question we are forced to ask... is not whether disruption is a legitimate tactic, but whether its use as a tactic in a particular context is legitimate.

Disruptions to Parliament are not new. During the UPA-II regime, the BJP-led opposition was guilty of employing the very same tactic to great effect. Owing to disruptions, the 15th Lok Sabha functioned at only 61% of its productive time, while the Rajya Sabha functioned at 66%.

Arun Jaitley would famously go on to defend parliamentary disruption as a legitimate tactic arguing:

"If parliamentary accountability is subverted and a debate is intended to be used merely to put a lid on parliamentary accountability, [disruption] is then a legitimate tactic for the Opposition to expose the government..."

The question we are forced to ask, therefore, is not whether disruption is a legitimate tactic, but whether its use as a tactic in a particular context is legitimate or not. In the preceding Monsoon Session, disruptions were made to initiate inquiries against the Madhya Pradesh government in light of the Vyapam Scam as well as Sushma Swaraj and Vasundhara Raje over LalitGate. Now, by Jaitley's logic, to disrupt Parliament over 40 mysterious deaths, or the Foreign Minister's role in abetting an economic offender's escape, might appear (subjectively) valid and legitimate.

In this session, disruptions over the constitutional crisis in Arunachal Pradesh may also be justified as it brought into light an issue that was otherwise being ignored. However, the other motivations for disruption can be termed vague at best and nebulous at worst. The fact remains that the alleged "political vendetta" was a judicial matter. The spillover into Parliament seems unwarranted, particularly when several government leaders in both Houses were happy to invite questions and debate on the issue.

In private, the younger brigade of Congress MPs admit that disruption shouldn't have gone on for more than three days. Furthermore, to disrupt Parliament over petty issues like Kumari Selja facing intolerance in a Gujarat temple and Jaitley calling her a liar, seemed ridiculous.

This winter session, parliamentary disruption had clearly overstayed its welcome. As a consequence, the productivity of the Rajya Sabha stood at only 46%...

Similarly, on 22 December, after the passage of the Juvenile Justice Bill, the opposition wanted to adjourn for the day, but the government was keen on progressing with the passage of the next bill. The opposition, clearly in no mood to work for a few hours more, proceeded to the well of the house shouting slogans asking for the resignation of Finance Minister Arun Jaitley over the DDCA scam.

This winter session, parliamentary disruption had clearly overstayed its welcome. As a consequence, the productivity of the Rajya Sabha stood at only 46% with the passage of only nine bills, with several key legislations, such as the Real Estate Bill, Whistleblowers Bill etc not being passed.

2. Legislating without debating

Ironically, while the BJP lambasted the Opposition for foul play and the use of disruptive tactics to evade debate, the other major issue that plagued this session was the lack of debate in the Rajya Sabha on several important bills. Interestingly, the government and its floor managers were actively campaigning to pass bills without debate.

In the Rajya Sabha, several important legislations like the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Bill, Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Bill, 2015, Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2015 and the Atomic Energy (Amendment) Bill, 2015 were passed with no debate.

The word "Parliament" has its etymological origins in the French and Latin words for "talk", which best exemplifies the true nature of the institution as the deliberative pillar of any democracy. Parliamentary democracy is based on the idea that a process of debate and discussion must buttress any State decision. This process seeks to hear from every side of the political spectrum.

Interestingly, the government and its floor managers were actively campaigning to pass bills without debate.

In the historical context of India, nothing exemplifies this better than the Constituent Assembly debates, which were the precursor to our Constitution. The Constituent Assembly debates lasted almost three years, yet the Constitution saw its first amendment as early as a year after its implementation.

This is clearly indicative of democracy as a dynamic process rather than an end in itself, and that dialogue is what drives this process. It is therefore a truism that legislative and policy decisions must be preceded by debate and discussion. However, this session saw a clear abdication of this duty on the part of our MPs.

3. Media influence precluding a balanced debate

In the context of the Juvenile Justice Bill, we witnessed the Parliamentary deliberation being adversely affected by a partisan media. While the more fundamental question surrounding the age of a juvenile might be a fair one to determine, the Parliamentary process failed to facilitate an unbiased and well-reasoned assessment of the question.

This can be attributed largely to the mainstream media, which had a hostile approach towards the issue. This is despite the fact that the Bill would not apply retrospectively to the juvenile in the Nirbhaya case. As a result of the intense media campaign, the BJP government decided to not pay heed to the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development's report, which rejected the bill, citing several constitutional infirmities.

Furthermore, discussion remained largely hyperbolic and hasty, while the proposals to send the Bill to a Select Committee were rejected. An MP told us in a private that while he was fundamentally against the JJ Bill, he feared being labelled "pro-rape" by his political opponents and the media. It was this fear and aggressively "pro" stance from the mainstream media that pushed a rather one-sided view through the Parliamentary process.

An MP told us in a private that while he was fundamentally against the JJ Bill, he feared being labelled "pro-rape" by his political opponents and the media.

The Bill posed a complex question that struck at the moral and constitutional fibre of the nation, warranting a far more extensive and balanced analysis. However, the mainstream media failed to provide that, capitalising on public sentiment, which led to the government and opposition succumbing to a less than informed public demand. In the context of the release of the juvenile convicted in the Nirbhaya case, the media perpetuated a one-sided perspective, which invariably led to a frenzied public campaign and hasty decision-making.

While one can argue whether the consequences of such a law are good or bad, one certainly can't deny that the means of enacting it were problematic.

As Narayan Ramachandran writes in Mint:

"When a self-righteous, vigilante society picks up an issue that is selectively amplified by the press, the risk of making policy detrimental to long-term interests is very high. The role of Parliament in this context is to be a deliberative body, not an echo chamber."

4. Poor floor management

The winter session was witness to poor floor management on many occasions. For example, on the last two days of Parliament, we saw three supplementary additions to the List of Business, in addition to the Revised List. The Payment of Bonus Bill was brought in for passage on the afternoon of the 23rd and passed in a few minutes without debate! By the lunch break, the Congress senior leadership in the Rajya Sabha were left scampering for a bill brief to review whether the Bill had any controversial aspects before formulating their party position.

In the Rajya Sabha, the Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Bill 2013 ended up having to go the Select Committee after it was pointed out that some of its provisions clashed with those of the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act 2013. This is poor management and should have ideally been anticipated by the government before listing it for consideration and passage. Oversight like this is an impediment to an efficient Parliamentary process.

The Payment of Bonus Bill was brought in for passage on the afternoon of the 23rd and passed in a few minutes without debate!

The Finance Minister also introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code and a Joint Committee has been set up to review the amendment, in relation to conflicting laws. When the Bill is passed in the budget session, this would be a vital reform as Indian PSUs are currently saddled with NPAs. However, within two days of introduction, the government was looking to pass the bill. This is an unwelcome move and MPs should ideally have been given enough time to study the finer details.

5. Parliamentary intolerance

The other big disappointment this session was Shashi Tharoor not being allowed to introduce his Private Member's Bill (PMB). Congress MP Tharoor was going to introduce a PMB to amend Section 377 of the IPC and decriminalise "consensual sex between consenting adults". However, just when he was about to introduce the Bill, BJP MP Nishikant Dube decided to prevent him, and after calling for a vote in the house (71 against, 24 for), Tharoor's Bill was disallowed even from introduction.

Tharoor clearly didn't see that coming and had no time to rally for support. Attendance is usually low on Friday afternoons as MPs fly back to their respective constituencies after attending question and zero hours. PMBs are introduced every alternate Friday and introduction of this Bill would not have in any manner meant an immediate amendment to Section 377.

To not allow the introduction of a PMB [Tharoor's, to amend Section 377] is arguably the highest form of parliamentary intolerance.

To not allow the introduction of a PMB is arguably the highest form of parliamentary intolerance. Even the introduction wouldn't have assured a discussion. PMBs for discussion are chosen through a ballot, and as legislative analyst Aparna Gupta puts it, "the chance of a bill coming up for discussion is harder a gamble than hitting a jackpot in a casino slot machine."

If a Bill does eventually come up for discussion (it is valid for three years after introduction), passing it is an even more herculean a task. Since independence, only 14 PMBs have been passed. The almost unanimous rejection of the Bill is surprising as PMBs are not "political" and a party stand or whip are not in play, at all. Employing such an aggressive stance seemed unfair to Tharoor, proving to be yet another instance of the majority being unnecessarily parochial and regressive.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |  Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter | Also on HuffPost: